Cambridge engineer who helped put man on the moon recognised with blue plaque

The Cambridge & District Blue Plaque Scheme recognises people and events that have made a significant impact on the area, the UK or, indeed, the world. It is run by local charity, Cambridge Past, Present & Future.

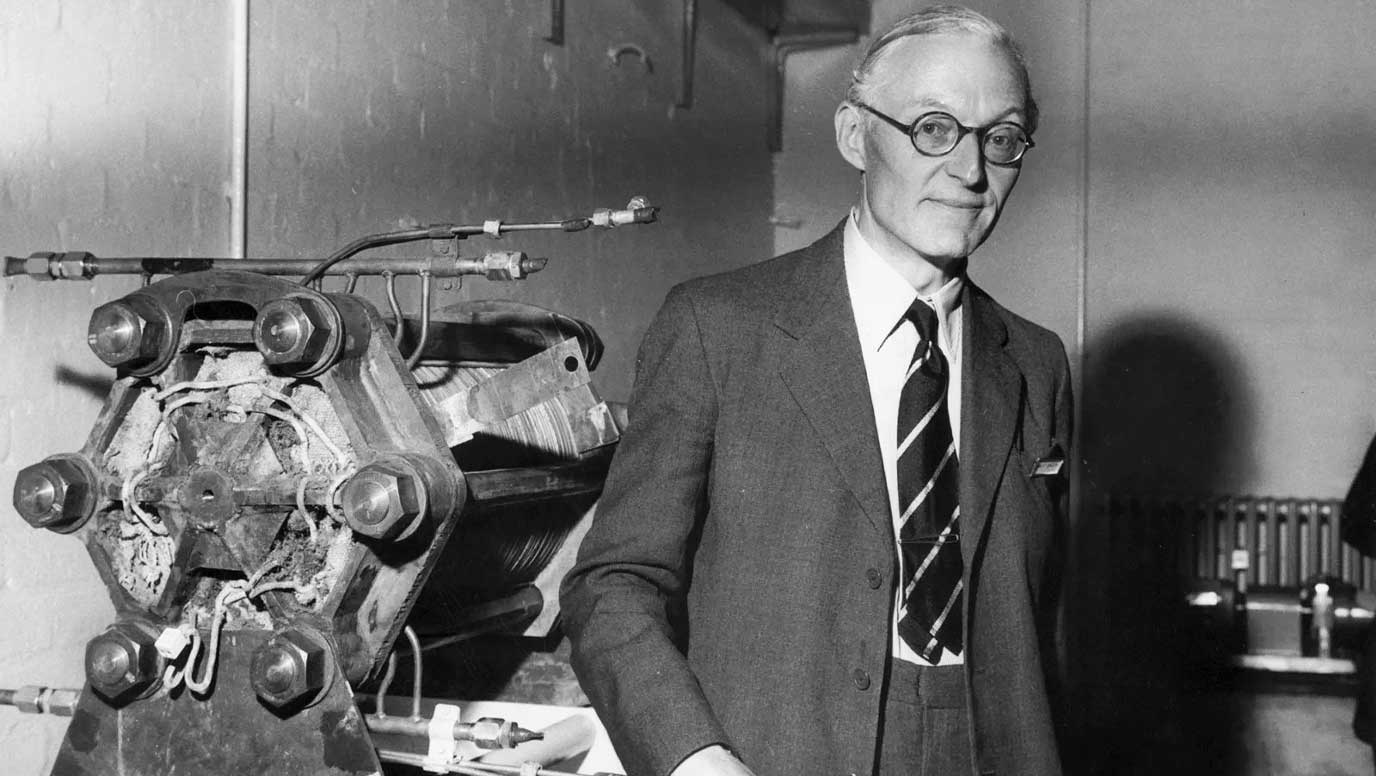

Tom Bacon developed the first practical working hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell. His fuel cells provided the secondary power for the Apollo Missions producing the electricity for the communications, air conditioning and lighting as well as drinking water for the astronauts. The Apollo 11 mission landed the first man on the moon in 1969.

“Without you Tom, we wouldn’t have gotten to the moon,” President Nixon famously said when he met Tom, who lived in Little Shelford near Cambridge from 1946 until his death in 1992. He developed the fuel cell at Cambridge University and later in partnership with Marshall of Cambridge.

Professor Clemens Kaminski, Head of the Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology (CEB) at the University of Cambridge, said: “Tom’s life work on fuel cells represents the spirit of innovation and sustainability that drives our department today.

“Long before terms like ‘clean energy’ and ‘sustainable technology’ were commonplace, Tom was harnessing fundamental science to address some of the world’s most pressing challenges.

“His invention not only helped put man on the moon, but also laid the foundation for the hydrogen fuel technology we continue to develop in our pursuit of a more sustainable future.”

After the success of the Apollo 11 mission, Tom and his wife Barbara were invited to 10 Downing Street to meet the three Apollo 11 astronauts, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins.

The fuel cell was co-developed at Marshall of Cambridge, where the blue plaque for Tom Bacon was today being unveiled.

Christopher Walkinshaw, Marshall’s Group Director of External Relations and Communications, said: “Tom Bacon was an exceptional engineer whose vision helped humanity reach the moon. We are delighted that he is being honoured with a blue plaque, and are very proud of Marshall’s role in the development and successful demonstration of his revolutionary fuel cell technology.”

Tom Bacon’s son, Edward, said: “My father was determined, close to being single-minded, in his dogged perseverance to advance the case for fuel cells.

“He was quiet, even-tempered and disarmingly modest, tending to underplay his considerable achievements and deflect any praise onto other people. Although he was proud and relieved that the fuel cells had performed so well in the Apollo Missions, he really wanted to see fuel cells in more down-to-earth applications like distributed power generation, energy supply in remote locations, emergency power and transport.

“Following his work, fuel cells have started to be used in some of these applications, especially in North America, China, Japan and South Korea. With the onset of climate change, he foresaw that fuel cells could contribute to a reduction in the output of carbon dioxide.”

The 41st plaque will be installed on the High Street, Little Shelford near Cambridge, where Tom once lived.

Francis Thomas Bacon (known as Tom) was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, taking the Mechanical Sciences Tripos in 1925.

After Cambridge he became an apprentice with C. A. Parsons & Co. Ltd, in Newcastle. Inspired by articles in the periodical Engineering in 1932, Bacon began to contemplate the possibility of storing energy in the form of hydrogen and releasing it as electricity. In 1839 Sir William Grove had first demonstrated the concept of a fuel cell.

A fuel cell is a device that produces electricity from the chemical reaction of a fuel and an oxidant which, unlike a battery, are supplied continuously from outside the cell. One hundred years later, Bacon was able to take Grove’s initial investigations further, using his experience as an engineer.

His original experiments were carried out secretly at Parsons but when he was discovered he was told either to stop them as not being relevant to the business or to leave; he left.

His father had settled a portion of the family estate on him at an early age and this gave him the financial means to pursue his scientific goals throughout his life.

During World War II, he started some initial experiments at King’s College, London. As it was thought that fuel cells could not be developed in time for War use, Bacon was then transferred to the Anti-submarine Research Establishment on the Clyde.

In 1946 the Electrical Research Association agreed to sponsor fuel cell research and he and his wife, Barbara, moved to Little Shelford, near Cambridge, with their three children. From 1946 to 1955 he continued his fuel cell work successively in the Departments of Colloid Science, Metallurgy, and Chemical Engineering at Cambridge University.

Although a six-cell 150-watt unit was demonstrated at a London exhibition, no interest was shown by industry; the team was disbanded and the apparatus was transferred to an outhouse at Bacon’s home in Little Shelford.

After an anxious six months of inactivity, the National Research Development Corporation agreed to finance further development of the Bacon fuel cell in 1957.

Sir Arthur Marshall, of Marshall of Cambridge, provided the necessary facilities, as he recalled in ‘The Marshall Story’, “A contract was established whereby Tom would provide the technical input and team up with Marshall with the object of developing a reliable, automatically controlled fuel cell to generate higher power than the lighting of a few bulbs which had previously been achieved under laboratory conditions. This was an exciting and challenging project.”

Bacon worked with a very competent team of engineers and chemists at Marshall to develop a 6 kW system which was demonstrated to the press in 1959.

The Bacon fuel cell was perfect for powering NASA’s spacecraft: it was lighter and much less bulky than batteries of the time, it was more efficient than 1960s solar panels, and hydrogen and oxygen were already going to be on board the spacecraft for use as rocket fuel. In addition, the only waste product from the reaction was water which was used as drinking water for the astronauts.

A prototype of one of the electrodes developed by Bacon is on display at the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, in Cambridge. His papers are in the Churchill Archives Centre of Churchill College, Cambridge.